A myriad of maladies. Fatherless children are at a dramatically greater risk of drug and alcohol abuse, mental illness, suicide, poor educational performance, teen pregnancy, and criminality.

Source: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Health Statistics, Survey on Child Health, Washington, DC, 1993.

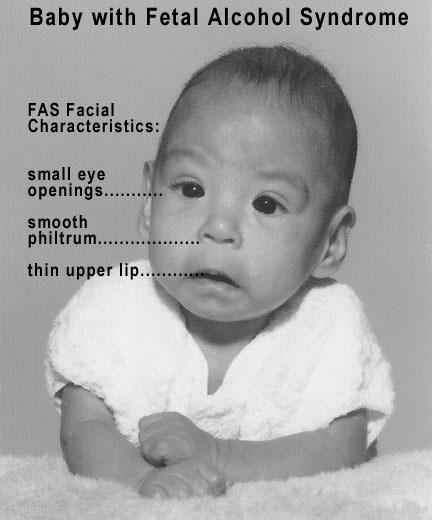

Drinking problems. Teenagers living in single-parent households are more likely to abuse alcohol and at an earlier age compared to children reared in two-parent households

Source: Terry E. Duncan, Susan C. Duncan and Hyman Hops, "The Effects of Family Cohesiveness and Peer Encouragement on the Development of Adolescent Alcohol Use: A Cohort-Sequential Approach to the Analysis of Longitudinal Data,"Journal of Studies on Alcohol 55 (1994).

Drug Use: "...the absence of the father in the home affects significantly the behavior of adolescents and results in the greater use of alcohol and marijuana."

Source: Deane Scott Berman, "Risk Factors Leading to Adolescent Substance Abuse," Adolescence 30 (1995)

Sexual abuse. A study of 156 victims of child sexual abuse found that the majority of the children came from disrupted or single-parent homes; only 31 percent of the children lived with both biological parents. Although stepfamilies make up only about 10 percent of all families, 27 percent of the abused children lived with either a stepfather or the mother's boyfriend.

Source: Beverly Gomes-Schwartz, Jonathan Horowitz, and Albert P. Cardarelli, "Child Sexual Abuse Victims and Their Treatment," U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

Child Abuse. Researchers in Michigan determined that "49 percent of all child abuse cases are committed by single mothers."

Source: Joan Ditson and Sharon Shay, "A Study of Child Abuse in Lansing, Michigan," Child Abuse and Neglect, 8 (1984).

Deadly predictions. A family structure index -- a composite index based on the annual rate of children involved in divorce and the percentage of families with children present that are female-headed -- is a strong predictor of suicide among young adult and adolescent white males.

Source: Patricia L. McCall and Kenneth C. Land, "Trends in White Male Adolescent, Young-Adult and Elderly Suicide: Are There Common Underlying Structural Factors?" Social Science Research 23, 1994.

High risk. Fatherless children are at dramatically greater risk of suicide.

Source: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Health Statistics, Survey on Child Health,Washington, DC, 1993.

Suicidal Tendencies. In a study of 146 adolescent friends of 26 adolescent suicide victims, teens living in single-parent families are not only more likely to commit suicide but also more likely to suffer from psychological disorders, when compared to teens living in intact families.

Source: David A. Brent, et al. "Post-traumatic Stress Disorder in Peers of Adolescent Suicide Victims: Predisposing Factors and Phenomenology." Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 34, 1995.

Confused identities. Boys who grow up in father-absent homes are more likely that those in father-present homes to have trouble establishing appropriate sex roles and gender identity.

Source: P.L. Adams, J.R. Milner, and N.A. Schrepf, Fatherless Children, New York, Wiley Press, 1984.

Psychiatric Problems. In 1988, a study of preschool children admitted to New Orleans hospitals as psychiatric patients over a 34-month period found that nearly 80 percent came from fatherless homes.

Source: Jack Block, et al. "Parental Functioning and the Home Environment in Families of Divorce," Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 27 (1988)

Emotional distress. Children living with a never-married mother are more likely to have been treated for emotional problems.

Source: L. Remez, "Children Who Don't Live with Both Parents Face Behavioral Problems," Family Planning Perspectives(January/February 1992).

Uncooperative kids. Children reared by a divorced or never-married mother are less cooperative and score lower on tests of intelligence than children reared in intact families. Statistical analysis of the behavior and intelligence of these children revealed "significant detrimental effects" of living in a female-headed household. Growing up in a female-headed household remained a statistical predictor of behavior problems even after adjusting for differences in family income.

Source: Greg L. Duncan, Jeanne Brooks-Gunn and Pamela Kato Klebanov, "Economic Deprivation and Early Childhood Development," Child Development 65 (1994).

Unstable families, unstable lives. Compared to peers in two-parent homes, black children in single-parent households are more likely to engage in troublesome behavior, and perform poorly in school.

Source: Tom Luster and Hariette Pipes McAdoo, "Factors Related to the Achievement and Adjustment of Young African-American Children." Child Development 65 (1994): 1080-1094

Beyond class lines. Even controlling for variations across groups in parent education, race and other child and family factors, 18- to 22-year-olds from disrupted families were twice as likely to have poor relationships with their mothers and fathers, to show high levels of emotional distress or problem behavior, [and] to have received psychological help.

Source: Nicholas Zill, Donna Morrison, and Mary Jo Coiro, "Long Term Effects of Parental Divorce on Parent-Child Relationships, Adjustment and Achievement in Young Adulthood." Journal of Family Psychology 7 (1993).

Fatherly influence. Children with fathers at home tend to do better in school, are less prone to depression and are more successful in relationships. Children from one-parent families achieve less and get into trouble more than children from two parent families.

Source: One Parent Families and Their Children: The School's Most Significant Minority, conducted by The Consortium for the Study of School Needs of Children from One Parent Families, co sponsored by the National Association of Elementary School Principals and the Institute for Development of Educational Activities, a division of the Charles F. Kettering Foundation, Arlington, VA., 1980

Divorce disorders. Children whose parents separate are significantly more likely to engage in early sexual activity, abuse drugs, and experience conduct and mood disorders. This effect is especially strong for children whose parents separated when they were five years old or younger.

Source: David M. Fergusson, John Horwood and Michael T. Lynsky, "Parental Separation, Adolescent Psychopathology, and Problem Behaviors," Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 33 (1944).

Troubled marriages, troubled kids. Compared to peers living with both biological parents, sons and daughters of divorced or separated parents exhibited significantly more conduct problems. Daughters of divorced or separated mothers evidenced significantly higher rates of internalizing problems, such as anxiety or depression.

Source: Denise B. Kandel, Emily Rosenbaum and Kevin Chen, "Impact of Maternal Drug Use and Life Experiences on Preadolescent Children Born to Teenage Mothers," Journal of Marriage and the Family56 (1994).

Hungry for love. "Father hunger" often afflicts boys age one and two whose fathers are suddenly and permanently absent. Sleep disturbances, such as trouble falling asleep, nightmares, and night terrors frequently begin within one to three months after the father leaves home.

Source: Alfred A. Messer, "Boys Father Hunger: The Missing Father Syndrome," Medical Aspects of Human Sexuality, January 1989.

Disturbing news: Children of never-married mothers are more than twice as likely to have been treated for an emotional or behavioral problem.

Source: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Health Statistics, National Health Interview Survey, Hyattsille, MD, 1988

Poor and in trouble: A 1988 Department of Health and Human Services study found that at every income level except the very highest (over $50,000 a year), children living with never-married mothers were more likely than their counterparts in two-parent families to have been expelled or suspended from school, to display emotional problems, and to engage in antisocial behavior.

Source: James Q. Wilson, "In Loco Parentis: Helping Children When Families Fail Them," The Brookings Review, Fall 1993.

Fatherless aggression: In a longitudinal study of 1,197 fourth-grade students, researchers observed "greater levels of aggression in boys from mother-only households than from boys in mother-father households."

Source: N. Vaden-Kierman, N. Ialongo, J. Pearson, and S. Kellam, "Household Family Structure and Children's Aggressive Behavior: A Longitudinal Study of Urban Elementary School Children," Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 23, no. 5 (1995).

Act now, pay later: "Children from mother-only families have less of an ability to delay gratification and poorer impulse control (that is, control over anger and sexual gratification.) These children also have a weaker sense of conscience or sense of right and wrong."

Source: E.M. Hetherington and B. Martin, "Family Interaction" in H.C. Quay and J.S. Werry (eds.), Psychopathological Disorders of Childhood. (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1979)

Crazy victims: Eighty percent of adolescents in psychiatric hospitals come from broken homes.

Source: J.B. Elshtain, "Family Matters...", Christian Century, July 1993.

Duh to dead: "The economic consequences of a [father's] absence are often accompanied by psychological consequences, which include higher-than-average levels of youth suicide, low intellectual and education performance, and higher-than-average rates of mental illness, violence and drug use."

Source: William Galston, Elaine Kamarck. Progressive Policy Institute. 1993

Expelled: Nationally, 15.3 percent of children living with a never-married mother and 10.7 percent of children living with a divorced mother have been expelled or suspended from school, compared to only 4.4 percent of children living with both biological parents.

Source: Debra Dawson, "Family Structure...", Journal of Marriage and Family, No. 53. 1991.

Violent rejection: Kids who exhibited violent behavior at school were 11 times as likely not to live with their fathers and six times as likely to have parents who were not married. Boys from families with absent fathers are at higher risk for violent behavior than boys from intact families.

Source: J.L. Sheline (et al.), "Risk Factors...", American Journal of Public Health, No. 84. 1994.

That crowd: Children without fathers or with stepfathers were less likely to have friends who think it's important to behave properly in school. They also exhibit more problems with behavior and in achieving goals.

Source: Nicholas Zill, C. W. Nord, "Running in Place," Child Trends, Inc. 1994.

Likeliest to succeed: Kids who live with both biological parents at age 14 are significantly more likely to graduate from high school than those kids who live with a single parent, a parent and step-parent, or neither parent.

Source: G.D. Sandefur (et al.), "The Effects of Parental Marital Status...", Social Forces, September 1992.

Worse to bad: Children in single-parent families tend to score lower on standardized tests and to receive lower grades in school. Children in single-parent families are nearly twice as likely to drop out of school as children from two-parent families.

Source: J.B. Stedman (et al.), "Dropping Out," Congressional Research Service Report No 88-417. 1988.

College odds: Children from disrupted families are 20 percent more unlikely to attend college than kids from intact, two-parent families.

Source: J. Wallerstein, Family Law Quarterly, 20. (Summer 1986)

On their own: Kids living in single-parent homes or in step-families report lower educational expectations on the part of their parents, less parental monitoring of school work, and less overall social supervision than children from intact families.

Source: N.M. Astore and S. McLanahan, Americican Sociological Review, No. 56 (1991)

Double-risk: Fatherless children -- kids living in homes without a stepfather or without contact with their biological father -- are twice as likely to drop out of school.

Source: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Survey on Child Health. (1993)

Repeat, repeat: Nationally, 29.7 percent of children living with a never-married mother and 21.5 percent of children living with a divorced mother have repeated at least one grade in school, compared to 11.6 percent of children living with both biological parents.

Source: Debra Dawson, "Family Structure and Children's Well-Being," Journals of Marriage and Family, No. 53. (1991).

Underpaid high achievers: Children from low-income, two-parent families outperform students from high-income, single-parent homes. Almost twice as many high achievers come from two-parent homes as one-parent homes.

Source: "One-Parent Families and Their Children;" Charles F. Kettering Foundation (1990).

Dadless and dumb: At least one-third of children experiencing a parental separation "demonstrated a significant decline in academic performance" persisting at least three years.

Source: L.M.C. Bisnairs (et al.), American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, no. 60 (1990)

Son of Solo: According to a recent study of young, non-custodial fathers who are behind on child support payments, less than half of these men were living with their own father at age 14.

Slip-sliding: Among black children between the ages of 6 to 9 years old, black children in mother-only households scored significantly lower on tests of intellectual ability, than black children living with two parents.

Source: Luster and McAdoo, Child Development 65. 1994.

Dadless dropouts: After taking into account race, socio-economic status, sex, age and ability, high school students from single-parent households were 1.7 times more likely to drop out than were their corresponding counterparts living with both biological parents.

Source: Ralph McNeal, Sociology of Education 88. 1995.

Takes two: Families in which both the child's biological or adoptive parents are present in the household show significantly higher levels of parental involvement in the child's school activities than do mother-only families or step-families.

Source: Zill and Nord, "Running in Place." Child Trends. 1994

Con garden: Forty-three percent of prison inmates grew up in a single-parent household -- 39 percent with their mothers, 4 percent with their fathers -- and an additional 14 percent lived in households without either biological parent. Another 14 percent had spent at last part of their childhood in a foster home, agency or other juvenile institution.

Source: US Bureau of Justice Statistics, Survey of State Prison Inmates. 1991

Criminal moms, criminal kids: The children of single teenage mothers are more at risk for later criminal behavior. In the case of a teenage mother, the absence of a father also increases the risk of harshness from the mother.

Source: M. Mourash, L. Rucker, Crime and Delinquency 35. 1989.

Rearing rapists: Seventy-two percent of adolescent murderers grew up without fathers. Sixty percent of America's rapists grew up the same way.

Source: D. Cornell (et al.), Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 5. 1987. And N. Davidson, "Life Without Father," Policy Review. 1990.

Crime and poverty: The proportion of single-parent households in a community predicts its rate of violent crime and burglary, but the community's poverty level does not.

Source: D.A. Smith and G.R. Jarjoura, "Social Structure and Criminal Victimization," Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency25. 1988.

Marriage matters: Only 13 percent of juvenile delinquents come from families in which the biological mother and father are married to each other. By contract, 33 percent have parents who are either divorced or separated and 44 percent have parents who were never married.

Source: Wisconsin Dept. of Health and Social Services, April 1994.

No good time: Compared to boys from intact, two-parent families, teenage boys from disrupted families are not only more likely to be incarcerated for delinquent offenses, but also to manifest worse conduct while incarcerated.

Source: M Eileen Matlock et al., "Family Correlates of Social Skills..." Adolescence 29. 1994.

Count 'em: Seventy percent of juveniles in state reform institutions grew up in single- or no-parent situations.

Source: Alan Beck et al., Survey of Youth in Custody, 1987, US Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1988.

The Main Thing: The relationship between family structure and crime is so strong that controlling for family configuration erases the relationship between race and crime and between low income and crime. This conclusion shows up time and again in the literature.

Source: E. Kamarck, William Galston, Putting Children First, Progressive Policy Inst. 1990

Examples: Teenage fathers are more likely than their childless peers to commit and be convicted of illegal activity, and their offenses are of a more serious nature.

Source: M.A. Pirog-Good, "Teen Father and the Child Support System," in Paternity Establishment, Institute for research on Poverty, Univ. of Wisconsin. 1992.

The 'hood The likelihood that a young male will engage in criminal activity doubles if he is raised without a father and triples if he lives in a neighborhood with a high concentration of single-parent families.

Source: A. Anne Hill, June O'Neill, "Underclass Behaviors in the United States," CUNY, Baruch College. 1993

Bringing the war back home The odds that a boy born in America in 1974 will be murdered are higher than the odds that a serviceman in World War II would be killed in combat.

Source: US Sen. Phil Gramm, 1995

Get ahead at home and at work: Fathers who cared for their children intellectual development and their adolescent's social development were more like to advance in their careers, compared to men who weren't involved in such activities.

Source: J. Snarey, How Fathers Care for the Next Generation.Harvard Univ. Press.

Diaper dads: In 1991, about 20 percent of preschool children were cared for by their fathers -- both married and single. In 1988, the number was 15 percent.

Source: M. O'Connell, "Where's Papa? Father's Role in Child Care," Population Reference Bureau. 1993.

Without leave: Sixty-three percent of 1500 CEOs and human resource directors said it was not reasonable for a father to take a leave after the birth of a child.

Source: J.H. Pleck, "Family Supportive Employer Policies," Center for research in Women. 1991.

Get a job: The number of men who complain that work conflicts with their family responsibilities rose from 12 percent in 1977 to 72 percent in 1989. Meanwhile, 74 percent of men prefer a "daddy track" job to a "fast track" job.

Source: James Levine, The Fatherhood Project.

Long-distance dads: Twenty-six percent of absent fathers live in a different state than their children.

Source: US Bureau of the Census, Statistical Brief . 1991.

Cool Dad of the Week: Among fathers who maintain contact with their children after a divorce, the pattern of the relationship between father-and-child changes. They begin to behave more like relatives than like parents. Instead of helping with homework, nonresident dads are more likely to take the kids shopping, to the movies, or out to dinner. Instead of providing steady advice and guidance, divorced fathers become "treat dads."

Source: F. Furstenberg, A. Cherlin, Divided Families . Harvard Univ. Press. 1991.

Older's not wiser: While 57 percent of unwed dads with kids no older than two visit their children more than once a week, by the time the kid's seven and a half, only 23 percent are in frequent contact with their children.

Source: R. Lerman and Theodora Ooms, Young Unwed Fathers . 1993.

Ten years after: Ten years after the breakup of a marriage, more than two-thirds of kids report not having seen their father for a year.

Source: National Commission on Children, Speaking of Kids. 1991.

No such address: More than half the kids who don't live with their father have never been in their father's house.

Source: F. Furstenberg, A. Cherlin, Divided Families. Harvard Univ. Press. 1991.

Dadless years: About 40 percent of the kids living in fatherless homes haven't seen their dads in a year or more. Of the rest, only one in five sleeps even one night a month at the father's home. And only one in six sees their father once or more per week.

Source: F. Furstenberg, A. Cherlin, Divided Families. Harvard Univ. Press. 1991.

Measuring up? According to a 1992 Gallup poll, more than 50 percent of all adults agreed that fathers today spend less time with their kids than their fathers did with them.

Source: Gallup national random sample conducted for the National Center for Fathering, April 1992.

Father unknown. Of kids living in single-mom households, 35 percent never see their fathers, and another 24 percent see their fathers less than once a month.

Source: J.A. Selzer, "Children's Contact with Absent Parents," Journal of Marriage and the Family, 50 (1988).

Missed contact: In a study of 304 young adults, those whose parents divorced after they left home had significantly less contact with their fathers than adult children who parents remained married. Weekly contact with their children dropped from 78 percent for still-married fathers to 44 percent for divorced fathers.

Source: William Aquilino, "Later Life Parental Divorce and Widowhood," Journal of Marriage and the Family 56. 1994.

Commercial breaks: The amount of time a father spends with his child -- one-on-one -- averages less than 10 minutes a day.

Source: J. P. Robinson, et al., "The Rhythm of Everyday Life." Westview Press. 1988

High risk: Overall, more than 75 percent of American children are at risk because of paternal deprivation. Even in two-parent homes, fewer than 25 percent of young boys and girls experience an average of at least one hour a day of relatively individualized contact with their fathers.

Source: Henry Biller, "The Father Factor..." a paper based on presentations during meetings with William Galston, Deputy Director, Domestic Policy, Clinton White House, December 1993 and April 1994.

Knock, knock: Of children age 5 to 14, 1.6 million return home to houses where there is no adult present.

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census, "Who's Minding the Kids?" Statistical Brief. April 1994.

Who said talk's cheap? Almost 20 percent of sixth- through twelfth-graders have not had a good conversation lasting for at least 10 minutes with at least one of their parents in more than a month.

Source: Peter Benson, "The Troubled Journey." Search Institute. 1993.

Justified guilt. A 1990 L.A. Times poll found that 57 percent of all fathers and 55 percent of all mothers feel guilty about not spending enough time with their children.

Source: Lynn Smith and Bob Sipchen, "Two Career Family Dilemma," Los Angeles Times, Aug. 12, 1990.

Who are you, mister? In 1965, parents on average spent approximately 30 hours a week with their kids. By 1985, the amount of time had fallen to 17 hours.

Source: William Mattox, "The Parent Trap." Policy Review. Winter, 1991.

Waiting Works: Only eight percent of those who finished high school, got married before having a child, and waited until age 20 to have that child were living in poverty in 1992.

Source: William Galston, "Beyond the Murphy Brown Debate." Institute for Family Values. Dec. 10, 1993.